This week, we will examine the Jeju language of South Korea. Home to the now ubiquitous K-pop and many cultural exports, as well as one of the most ethnically homogenous societies on Earth, Korea has a little-discussed language spoken on one of its most popular tourist destinations: Jeju Island. Despite its unique geographical position and culture, the language is almost on the verge of death. Join us as we take a look at Korean’s distant islander cousin.

Background

Jeju (제줏말/Jejunmal) is a critically endangered language spoken on the island of Jeju, located around 50 miles off the coast of the Korean peninsula. Although there is some debate, Jeju and Korean are generally regarded as the only extant members of the Koreanic language family. Due to its close relation to Korean, Jeju was often regarded as a dialect of Korean; however, the two languages are not mutually intelligible. Jeju is also one of only 3 languages in the world that use the Hangul writing system. Due to rapid language shift, only an estimated 5,000 speakers of Jeju are left.

History

The first signs of human settlement on Jeju date to around ten thousand years ago, with the first evidence of an organized polity being the Tamna kingdom. According to Vovin, the original inhabitants of Tamna were Japonic, but it was later conquered by proto-Korean invaders. However, we do know for sure that in 476 Tamna became a tributary of the Baekje kingdom on the mainland, later switching allegiance to the Silla kingdom. The island was annexed by the Goryeo in 1105 and later invaded by the Mongols, who held it for around one hundred years. In 1404, the island switched hands yet again to the Joseon, who prohibited its residents from leaving the island and brutally crushed uprisings throughout the 19th century. In 1520, Kim Jeong, author of the Topography of Jeju Island, visited the island and reported having difficulty understanding the island’s local speech – the first documented report we have of a difference between mainland Korean and Jeju. From 1910 to 1945, the island was occupied by the Japanese, but the worst event in the island’s history came during the Korean War. An event invariably tied to the history of Jeju that comes up with any discussion of it, the 4·3 incident or Jeju uprising was the worst atrocity in the island’s long history of repression. In response to an insurgency by communist rebels around Hallasan Mountain, for months, Korean soldiers and right-wing irregulars killed around 30,000 people – 10% of the island’s population. Entire villages were systematically eradicated as anyone in the island’s interior was considered a rebel, and most members of the local elite were wiped out. The events were persistently denied and covered up throughout the many decades of military rule in Korea, but a truth commission created in 2000 sought to bring reconciliation. Still, it remains a controversial matter, with many right-wing Koreans denying it or claiming it was deserved, while history textbooks have only recently included it in response to public pressure. While there is not much documentation of the language’s history in particular, all of these events let us glean how the island’s turbulent history led to the language’s almost moribund status today. Centuries of oppression and discrimination fostered linguistic diversity early on, but later discouraged people from speaking it and eventually contributed to its decline in usage.

Culture

Jeju is well known for its unique culture, with many customs and traditions that are not found on the mainland. Perhaps the most well-known of these are the dolhaleubang or ‘stone grandfathers’, large stone statues that represent good luck. The haenyeo or ‘sea women’ are also part of the island’s unique cultural heritage, diving into the ocean without any gear for chiefly abalone, a type of sea snail enjoyed as a delicacy on the island and in other cultures as well. Jeonbok-juk, or abalone rice porridge, is a local specialty of the island and one of its chief dishes. Jeju’s creation myth involves three demigods, Go, Yang, and Bu, who came out of the earth at a place called Samseonghyeol in Jeju City, marrying three princesses and beginning to cultivate the land, thus beginning the island’s history. Other pieces of recognized cultural heritage include chilmeolidanggus, a ritual of traditional Jeju shamanism, Mangeon headbands, Tangeon hats, and folk songs known as Jeju minyo. Traditions such as the island’s traditionally matriarchal family structure and the creation of stone structures such as jeongnang, bangsatap, and doldam also define the unique culture of Jeju Island.

Language

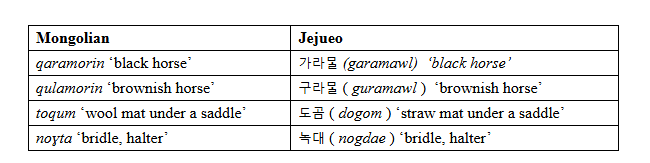

Jeju has no standard variety but can roughly be split into 2 dialects, one spoken in the north and one in the south of the island; a slight east-west divide also exists. The language has significant overlap with Korean in terms of phonology but uses a vastly different vocabulary, making it mutually unintelligible with standard Korean. In a 2014 study, speakers of Jeju and Korean were found to view both languages as similarly or even less intelligible than speakers of Dutch and Norwegian when exposed to a narrative in the language. Jeju has 9 vowels compared to Korean’s 8, as it preserves the vowel /ɒ/, found in Middle Korean but lost in modern Korean; it also preserves some elements of vowel harmony found in Middle Korean, containing 2 classes of vowels and a neutral /i/. Unlike Korean, however, Jeju has fewer levels of formality, around 4 compared to Korean’s 7. This has also contributed to traditional negative stereotypes of the language as being informal and impolite. Interestingly, Jeju has many Mongolian loanwords stemming from a century of Mongol rule over the island, primarily related to animal husbandry.

Modern Day

A popular notion in Korea, also espoused by the government, is that Koreans’ national identity is bound to a single shared language. This has undoubtedly had great consequences for Jeju, as it had been classified as a dialect of Korean until recently – even now, its status as a language is controversial to some. However, on a positive note, under its classification as a dialect, much research was still conducted on it by Korean experts. According to UNESCO estimates, around five to ten thousand islanders can speak the language, or around one to two percent of the population. Even this estimate is probably highly optimistic, as many of the few that can speak it only have limited fluency or spoke it in their youth but have lost most of their abilities. In general, the speaker base has been confined to the elderly.

Examples

In isolation, Jeju seems very similar to Korean, but I found it very productive to look at comparative studies of phrases in Korean and Jeju and see the differences between them. Some examples include:

Comparing a basic Jeju sentence with Korean:

‘A farmer was planting a tree.’

Korean: Nongbu namu sim-go iss-eoss-eo. (농부 나무 심고 있었어)

Jeju: Nongbani nang singg-eoms-eon. (농바니 낭 싱ᅥ언)

Part of a Jejuan creation myth:

Korean: Neo Song Saman-ineun gyeou seoleun-i sumyeong-ui kkeut-ini, seoleun doeneun haeeneun amu dal amu nal-e myeong-i kkeutnal teimeulo neoga bal-i sal-aseo umjig-il su iss-eul ttae naleul namusup-eulo delyeoda dalla (너 송사만이는 겨우 서른이 수명의 끝이니, 서른 되는 해에는 아무 달 아무 날에 명이 끝날 테이므로 너가 발이 살아서 움직일 수 있을 때 나를 나무숲으로 데려다 달라)

Jeju: Neu Song Sawman-i jeonmaeng-i gawt seoreun-i maeg-inan, seoreun naneun hae-e amu dawl amu nar-eun maeng-i maeg-ini neu-ga bal sarang omong-hawyeo-jil ttae, na-reul nang-gos-euro gawjyeoda dora (느 송ᄉᆞ만이 전맹이 ᄀᆞᆺ 서른이 매기난, 서른 나는 해에 아무ᄃᆞᆯ 아무날은 맹이 매기니 느가 발 살앙 오몽ᄒᆞ여질 때, 나를 낭곳으로 ᄀᆞ져다 도라)

Basic phrases:

밥 묵었수과? (bap mugeossukwa?): Have you eaten? (Fig: how are you?)

고맙수다 (gomapsuda): Thank you

반갑수다 (bangapsuda): Nice to meet you

멧 시우꽈? (met si-ukkwa?): What time is it?

미안ᄒᆞ다 (mianhawda): I’m sorry

일흠이 무신거우꽈? (ilheum-i musin’geo-ukkwa?): What is your name?

펜안ᄒᆞ우꽈 (pen-anhawukkwa): How are you/Hello

ᄒᆞᆫ저옵서예 (hawnjeo-op-seo-ye)/ᄒᆞᆫ저옵서양 (hawnjeo-op-seo-yang): Welcome

봅서 (bopseo): Hello

기여 (giyeo)/예 (ye): Yes

아니다 (amida)/말다 (malda): No

This website has many spoken conversations in Jeju: jeju-kim-0351 | Endangered Languages Archive

Conclusion

Despite the almost moribund status of Jeju, there are many efforts to preserve it that may bear fruit in the future. The Jeju Language Preservation Society was founded in 2008; in 2011 the government of Jeju approved the Language Act for the Preservation and Promotion of Jejueo, while the Jeju Office of Education also created a General Plan for Jejueo Conservation and Education in the same year. According to the authors of Jejueo, the conditions are ideal for a language revival, with there being strong support, documentation, and infrastructure in place that could spark a possible revival of the language. Only time can tell what the future may bring, but we can hope that, perhaps in the future, Jeju and Korean can coexist on the island.

Sources and Attributions:

Sources:

Yang, Changyong, et al. Jejueo: The Language of Korea’s Jeju Island. University of Hawai’i Press, 2020. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvwvr2qt. Accessed 20 Aug. 2025.

Kim, Hun Joon. The Massacres at Mt. Halla: Sixty Years of Truth Seeking in South Korea. Cornell University Press, 2014. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7591/j.ctt5hh0hs. Accessed 20 Aug. 2025.

Vovin, Alexander. From Koguryo to T’Amna.

Attributions (in order):

Public domain via NASA

Trainholic, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Screenshotted from Jejueo – Jejueo-English Basic Dictionary 제주어-영어 기초 사전

LG전자, CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Leave a comment