Today, we will go to the arid deserts of the southern tip of Africa to discuss the Khoekhoe language, straddling the Kalahari Desert through South Africa, Namibia, and Botswana. Long grouped together with the San, a people almost as old as time itself, only recently has Khoekhoe been recognized in its own regard, although both share features that are seldom found outside of this sparsely populated region, famously, a heavy use of complex click consonants. Join us as we explore a language with a rich history and many unique linguistic features.

Background

Khoekhoe (Khoekhoegowab), also known as Nama or Damara, is a Khoe language spoken throughout southwestern Africa. Khoe is a small language family that is thought to have originated from central Africa before migrating south to what is now the Kalahari and South African coast, differentiating from the nearby San due to their adoption of nomadic pastoralism compared to the San’s hunter-gatherer lifestyle. Until the late 20th century, the languages of the Khoe and San were grouped under Khoisan, but later research has proven the two are unrelated, therefore making the grouping outdated. Khoe languages used to be spoken throughout modern-day South Africa before being displaced by Dutch and British settlers or adopting their languages.

History

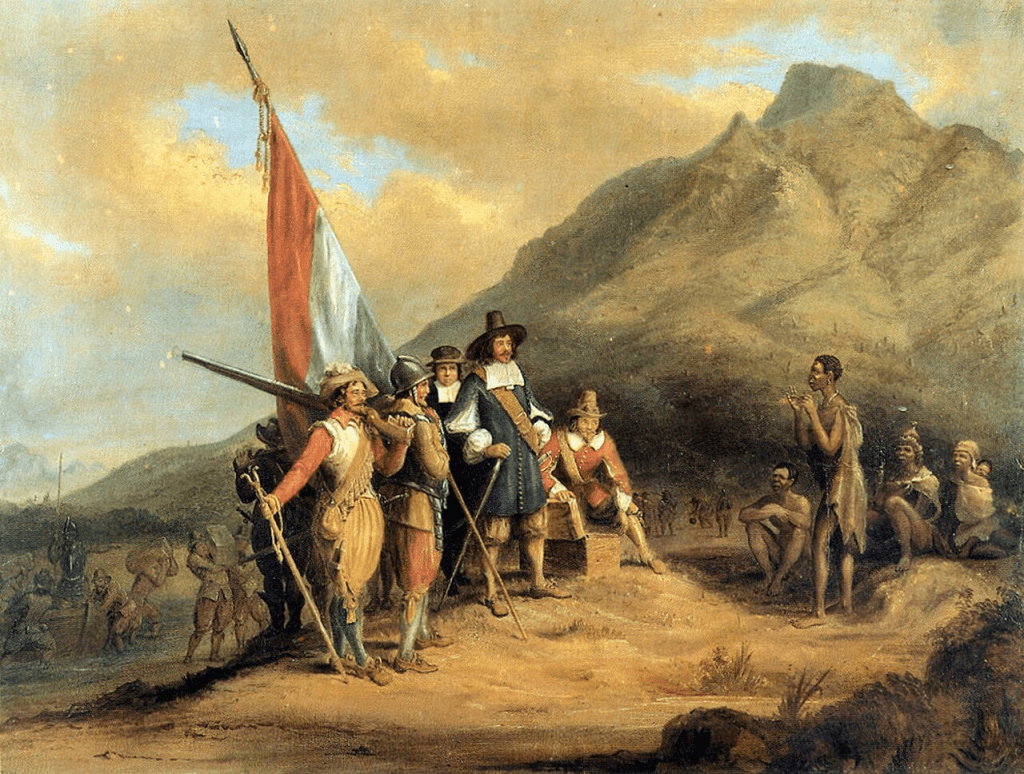

The Khoekhoe are thought to have migrated to South Africa and Namibia from the north thousands of years ago, in contrast to the even more ancient San people. The Khoekhoe were traditionally a nomadic people who herded sheep, goats, and cattle. Bantu groups such as the Nguni (including the Zulu and Xhosa) and Sotho had arrived by 1000 AD, adopting click consonants from extensive contact with Khoe and San peoples. Many place names in South Africa originate from Khoekhoe, even as far as territory inhabited by Bantu peoples, which is recognizable due to the usage of clicks. There also was extensive bilingualism, particularly between the Khoekhoe and Xhosa. In 1652, a supply post was founded by Jan van Riebeeck for the Dutch East India Company near modern-day Cape Town, beginning the process of European settlement in southern Africa. Early contact between the Dutch and Khoekhoe was facilitated through the use of Cape Dutch Pidgin, a sort of simplified form of Dutch that utilized some elements of Khoekhoe grammar. The Khoekhoe resisted Dutch control and enslavement through the Khoekhoe-Dutch Wars but were largely subjugated and assimilated, leading to rapid language loss and the creation of new communities such as the Griqua and Basters. Similar to the Mestizos of Latin America, the Griqua and Basters were the result of relations between mostly Dutch men and Khoekhoe women; they primarily spoke Afrikaans instead of Khoe languages. The Xiri (also known as Khoemana or Korana) language is still spoken by very few Griqua, and is almost extinct. Khoekhoe is still spoken in the Richtersveld area in South Africa, while it has been replaced by Afrikaans almost everywhere else in the former range of the Khoe peoples. The Cape Coloured community which makes up most of the interior Cape is a mixed community of mostly Khoe, European, and Asian descent.

From 1904 to 1908 the Herero and Nama genocide systematically eradicated thousands of Namas under the colonial German regime through intentional starvation and dehydration as well as the use of concentration camps. In 1980, the Nama (the predominant group of Khoekhoe speaking peoples) received nominal independence as the Bantustan of Namaland. The Bantustans were self-governing entities set aside for specific African communities, where it was planned to eventually deport all Africans. Namaland dissolved after South Africa agreed to grant Namibia independence in 1989, with the former territory being part of the new nation.

Culture

As mentioned before, the Khoekhoe are traditionally nomads who practiced pastoralism, particularly raising sheep and goats. The Khoekhoe traditionally lived in huts, known as matjieshuise, which were portable and well-suited to their nomadic lifestyle. Women traditionally played an important role in building these huts, while men were primarily responsible for herding livestock. The Richtersveld on the border between Namibia and South Africa is recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site for the transhumance traditions of the Nama people who live there. Khoekhoe culture was also rich in oral traditions, with stories, songs, and rituals passed down through generations.

Language

The Khoekhoe language is most notable for its extensive use of click consonants, which are seldom found outside of southern Africa. The 5 types of clicks in Khoekhoe are the bilabial, dental, alveolar, palatal, and lateral clicks, which can further be combined with other consonant sounds and released in various ways, creating a highly complex system of sounds unique to these languages. Khoekhoe in fact has 20 clicks and only 11 non-click sounds. Khoekhoe is also a tonal language and, like most languages, uses SOV word order.

Modern Day

Despite being the largest of its language family, Khoekhoe is becoming a vulnerable language. Khoekhoe is a recognized language in Namibia and South Africa, where most of its speakers live. In Botswana, many Khoekhoe speakers, especially among the youth, are shifting to Setswana, due to traditional stigma against Khoekhoe and extensive code-switching between Setswana and Khoekhoe. Compared to other African language families, research in Khoekhoe has only recently made significant breakthroughs and still remains to be studied further.

Examples

There are not many written materials in Khoekhoe; not even the Universal Declaration of Human Rights has been translated into the language. Here are some spoken examples on the internet that particularly demonstrate the unique click consonants:

Beautiful click consonants in Namibia’s Khoekhoe language | Emeloelaj speaking Nama | Wikitongues

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Khoekhoe-languages#/media/1/316784/68882

Conclusion

Khoekhoe represents a fascinating example of cross-linguistic contact and linguistic areas with its transmission of click consonants to other southern Bantu languages, for which they are famous, but one of the progenitors of the expansion of click consonants across this region is at risk. With parents not wanting their children enrolled in Khoekhoe schools, weakening an already small community, the Khoekhoe need further support and resources for the chain of language transmission to remain intact. Furthermore, the increase of globalization favouring English and Afrikaans also set Khoekhoe on unstable foundations, and there needs to be more research on the language. Despite all of these factors, there are already Khoekhoe schools, radio stations, and videos online teaching people how to speak it. There is hope that this rich tradition and language will continue to thrive in one of Earth’s most barren corridors.

Sources

“Language vitality among the Nama of Tshabong” (47-56). Batibo, Herman M. and Tsonope, Joseph (2000)

Barnard, A 2008, ‘‘Ethnographic analogy and the reconstruction of early Khoekhoe society’: Southern

African Humanities: A Journal of Cultural Studies’, Southern African Humanities, vol. 20, pp. 61-75.

Barnard, Alan. Hunters and Herders of Southern Africa: A Comparative Ethnography of the Khoisan Peoples. Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Leave a comment