Friulian is spoken in Friuli, a border region in northeastern Italy, which has long been a crossroads of cultures and conflicts, its Romance heritage disrupted in the sixth century under Germanic influence. Friulians are also an ethnically mixed people with Latin, Germanic, and Slavic heritage, owing to their position as a crossroads of cultures. Distinct from other Italo-Romance languages through features such as the loss of most final vowels, Friulian has a rich literary history dating back to the 13th century. Today, Friulian is spoken by over 700,000 people in the province of Friuli-Venezia Giulia and abroad. The language shows some geographic variation, with the central Friulian dialect forming the basis of the literary and official standard. Recognized as an official language in 1999, Friulian now holds protected status in the region, though its use is waning, especially among the urban youth.

History

A sense of strong local identity developed early in Friuli, especially under the Lombard Duchy (7th-9th centuries), and flourished during its “golden age” (10th-15th centuries) under the Patriarchs of Aquileia, who united religious and political power and even had a parliament. After Venice conquered the region around 1410, Friuli was allowed to keep some local institutions but lost most of its autonomy and suffered economic neglect, remaining rural and militarized as a frontier between Venice, Austria, and the Ottoman Empire. These conditions shaped Friuli’s culture and reputation, with Venetians often viewing Friulians as rough and backward. Linguistically, Friulian differs significantly from neighboring Venetian and Italian, though it was long overshadowed by Latin and Italian in writing. Some writers used Friulian for satire and folk literature, expressing local pride and their resistance to Venetian rule.

Friulian literature flourished through the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries with poets such as Girolamo Sirti, Giovan Battista Donato, and Eusebio Stella, whose works often incorporated diverse varieties of speech, reflecting the lack of a standardized variety of Friulian and the dialectal variation within the language, even in Renaissance times. Baroque writer Ermes Di Colloredo was one of the most important figures of Friulian literature, creating both poetry and prosaic works, mostly on the topic of love. In the 19th century, the movement of Romanticism also spurred a strong Friulian identity revival. Writers such as Pietro Zorutti and Pietro Bonini contributed to the push toward creating a literary standard for Friulian, with Zorutti creating a koine based on Udine’s dialect, and Bonini translating works. The Italian linguist G. I. Ascoli also played a key role, arguing that Friulian was not an Italian dialect, rather, that it was part of the Ladin—now known as the Rhaeto-Romance—language family, giving Friulian increased linguistic legitimacy.

During the 19th century, Friuli experienced political instability and economic hardship, shifting from Venetian to French, Austrian, and finally Italian rule, with famine and overpopulation worsening poverty. With little industry and harsh land, mass emigration, naturally, occurred. By 1961, nearly 400,000 Friulians had emigrated, creating ethnic associations known as Fogolârs abroad that retained ties to and supported their homeland, especially visible after the 1976 Friuli earthquake. In the 20th century, three major historical forces shaped Friulian identity: World War I, fascist rule, and the unification with Trieste. Fought largely in and around Friuli, WWI spurred intense Italian nationalist propaganda, portraying Friulians as patriotic defenders against Austria. While suppressing local autonomy, Mussolini’s regime paradoxically promoted Friulian folklore and culture as proof of Italy’s ancient Latin heritage. Finally, after WWII, Italy merged Friuli with Trieste, a historically Austrian, cosmopolitan port city with little real connection to Friuli. Despite strong Friulian opposition, the state formed the Friuli-Venezia Giulia region in 1963, one of five regions of Italy with home rule due to their linguistic and cultural diversity. This unhappy marriage bred political tension and resentment, fueling regionalist movements such as the Movimento Friuli.

Until about 1950, Friuli remained a largely rural and traditional peasant society, divided politically along class and geographic lines, with rural areas tending to be more left-leaning while the towns and cities supported the Christian Democrats. Post-1950 industrialization brought “suburbanization”, as people worked in new industries but kept rural homes and traditions, while economic modernization in the 1960s, driven by centralized planning, neglected mountain areas and fueled resentment toward “anti-Friulian” policies. Political and cultural conflicts emerged over military occupation, environmental degradation, and lack of a university in Friuli, leading to the birth of the aforementioned Movimento Friuli for autonomy and cultural protection, while tensions with southern Italian migrants further heightened Friulian distinctiveness. By the 1970s, these struggles turned Friuli into a center of regional consciousness and identity, with Friulian activism evolving into a multifaceted movement, despite often being dismissed as reactionary or provincial in nature. It was dominated by competing clerical, secular, and radical leftist currents, but the Movimento Friuli (MF), established in 1968, emerged as the biggest Friulian party, initially achieving notable electoral success but later declining due to internal conflicts and the co-optation of its platform by mainstream parties. The 1976 Friuli earthquake, which devastated the region, became a catalyst for cultural renewal and institutional reform, including the founding of the University of Udine. Friulian was formally recognized as a protected minority language in 1999. Since 1900, the region’s population has doubled, but is declining due to emigration and faltering birth rates.

Modern Day

Roughly 650,000 people continue to speak Friulian, though the language, never taught formally in schools and long confined to familial and communal environments, is rapidly declining as Italian dominates education, media, and work. With half of parents no longer passing Friulian to their children, its survival is now in great jeopardy. While there is widespread rhetorical support for greater Friulian autonomy and cultural preservation, political and constitutional barriers complicate proposals such as separating Friuli from Trieste within the regional government. Law 482 of 1999 officially recognized historical minority languages such as Friulian, Ladin, and Sardinian, permitting their use in education, administration, and media, marking a significant step toward safeguarding Italy’s minority languages and giving some assurance of Friulian’s continued presence in national life.

Language

The nasals /m, n, ŋ/ can vary: /n/ often becomes [ŋ] before pauses or certain consonants, and /m/ and /n/ assimilate to the following sound’s place of articulation (e.g., [m] before /p, b/). Final /ŋ/ may surface as [iŋ] or [in], and nasals can resyllabify before vowels or /j/. The dental affricates /t͡s/ and /d͡z/ appear mainly in Italian or Latin loanwords, but [t͡s] is now rare, replaced by [s] in central Friulian under Venetian and Italian influence. /d͡z/ is also declining, with most speakers favoring [z], though conservative northern and southern varieties preserve the affricate, especially word-initially. The post-alveolar /t͡ʃ/ may shift to [t͡s] or [s] in word-final –ce endings, again reflecting Venetian and modern influence. In central Friulian, the alveolar fricatives /s/ and /z/ contrast only at the beginning of syllables. Before consonants, they may shift to post-alveolar [ʃ, ʒ] or labialized forms [sʷ, zʷ], especially in casual speech. Word-final /s/ can become voiced before voiced sounds, but /z/ never occurs finally. The post-alveolar fricatives /ʃ, ʒ/ are now mostly confined to older speakers and merge with /s, z/ in modern urban varieties, though some contrasts survive. Word-initial /j/ normally remains [j], though it can alternate with [d͡ʒ] in certain words. Unstressed [j] may also alternate with [i] after consonants. The lateral /l/ assimilates to the following consonant’s place of articulation: [ʎ] before palatals (il cjan [iʎ caan] ‘the dog’) and [l̪] before dentals (alt [aal̪t] ‘high’). Otherwise, it stays [l]. Before /j/, it may resyllabify, yielding variants like al jeve [al ˈjeːve], [aˈljeːve], or [a lʲˈjeːve] (‘he gets up’).

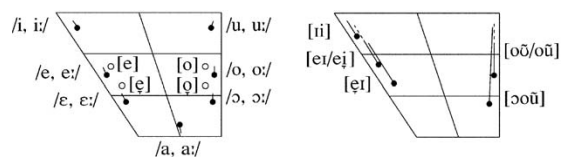

Central Friulian has seven main vowels, /i, e, ɛ, a, ɔ, o, u/ that can be short or long, effectively doubling its vowel inventory. Long vowels are more peripheral in sound and usually occur in stressed or word-final syllables, especially before certain consonants. In many positions (like in the middle of words or before /r/), vowel length differences have mostly disappeared. Long vowels can also form diphthongs, especially in plural forms, but this distinction is weakening in modern speech. Interestingly, the northern dialects often lower high vowels (/i/, /u/) to mid vowels (/e/, /o/), a process that can spread within words. Stress in Friulian usually stays fixed, except when small words (like pronouns or articles) attach to others. Similar to English, intonation can convey meaning: statements end with a falling tone, yes/no questions have a rising-falling tone, and continuing phrases have a rise-fall-rise pattern.

Examples

UDHR: Ducj i oms a nassin libars e compagns come dignitât e derits. A an sintiment e cussience e bisugne che si tratin un culaltri come fradis.

Pier Paolo Pasolini, Ciant da li ciampanis:

Co la sera a si pièrt ta li fontanis

il me país al è colòur smarít.

Jo i soj lontàn, recuardi li so ranis,

la luna, il trist tintinulà dai gris.

A bat Rosari, pai pras al si scunís:

jo i soj muàrt al ciant da li ciampanis.

Forèst, al me dols svualà par il plan,

no ciapà pòura: jo i soj un spìrit di amòur

che al so país al torna di lontàn.

Sources

Wikimedia Commons

Civici Musei Udine

Haller, Hermann W. The Other Italy: The Literary Canon in Dialect. University of Toronto Press, 2016.

“Rheto-romance studies.” The Year’s Work in Modern Language Studies, vol. 73, Jan. 2013, pp. 284–291, https://doi.org/10.5699/yearworkmodlang.73.2011.0284.

Strassoldo, Raimondo. “Regionalism and ethnicity.” International Political Science Review, vol. 6, no. 2, Apr. 1985, pp. 197–215, https://doi.org/10.1177/019251218500600205.

Illustrations of the IPA: Friulian

Leave a comment